In 2007, I visited Las Vegas at the invitation of college student Edgar Flores.

He volunteers at the Latino Youth Leadership Conference, an annual weeklong conference at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where he majors in English.

About 100 high school students came together to learn leadership skills and build a sense of identity in a state where Latinos were largely powerless at the time.

Seven days. seven states. Nearly 3,000 miles. Gustavo Arellano talks to Latinos in the Southwest about their hopes, fears and dreams this election year.

In a small auditorium, I told young people to know their history, to be proud of being Latino, and to never forget to mentor others. My talk must have resonated because I get invited back every few years.

Each time I came back, Flores was promoted: graduate student. Law School. Pass the bar exam. his own practice. Member of State Assembly. Now 38, he is a Democratic state senator.

In the more than 15 years since I first spoke there, the Latino Youth Leadership Conference has transformed into an incubator. Board members, state legislators and even members of Congress are alumni. business owner. Teacher, NASA engineer. Republicans, Democrats and everyone in between.

I have been fortunate to speak at similar youth conferences in the Southwest, which have been held since the 1930s. They profoundly impact Latino lives but receive little mainstream media coverage.

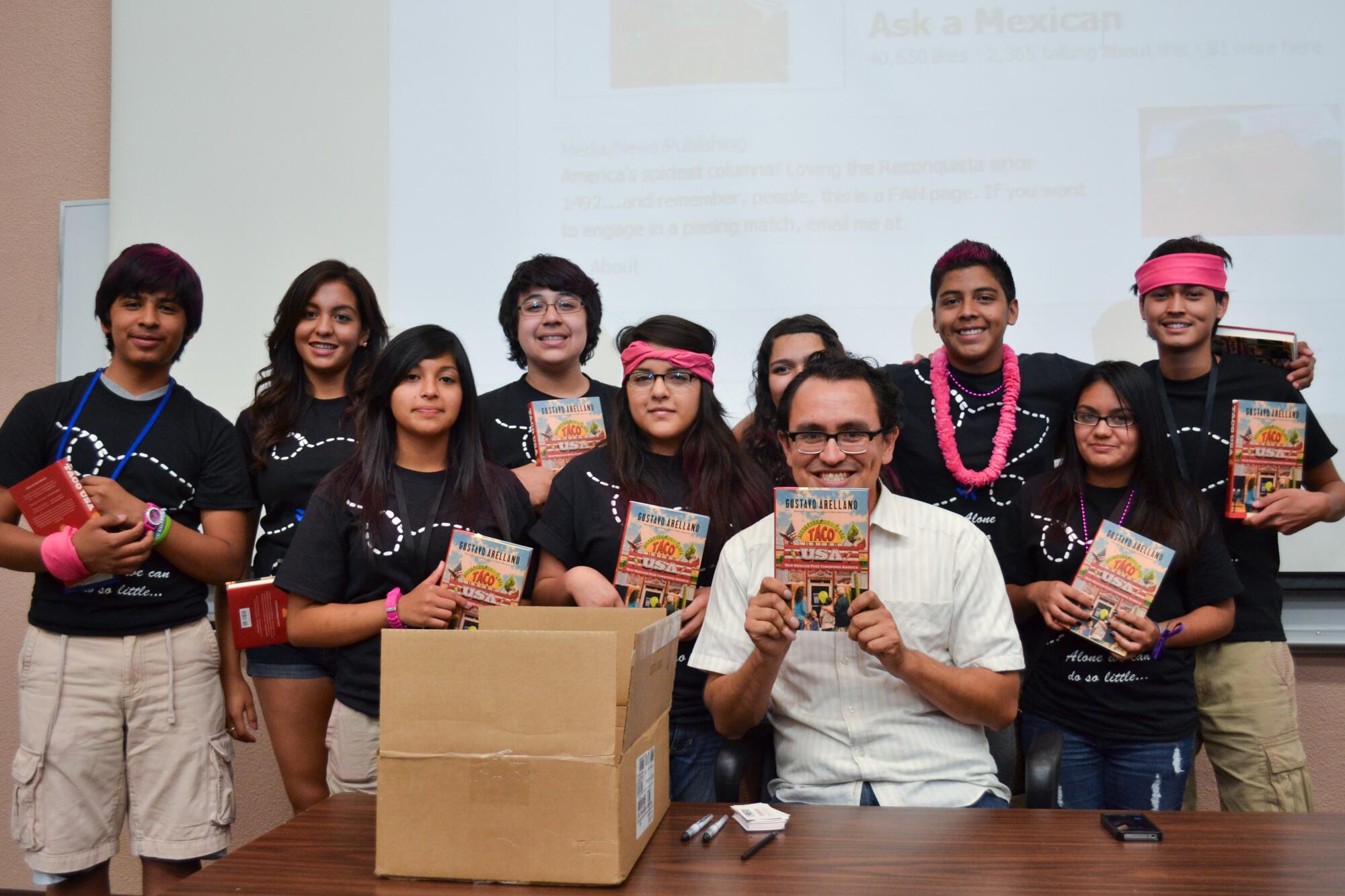

In 2012, The Times’s Gustavo Arellano joined students at a weeklong Latino youth leadership conference that was originally designed to get more Latinos into college and lower the High school dropout rate.

(Courtesy Edgar Flores)

On a road trip to talk to Latinos about their hopes and fears for this presidential election season, a visit to Flores was a must.

Plus, he knows where to eat in Vegas.

“Every time I go to a meeting, I always tell them, ‘Look to the left. Look to the right. You’re looking for the next CEO, you’re looking for elected officials, you’re looking for the president, you’re looking for business owners. If you accept this, you will take advantage of this opportunity ten times further,” he said.

“You just long to do something for your community,” said Irene Cepeda, 35, director of programs at Nevada State University and a former Clark County Board of Education trustee. She is a conference alumna and leads its nonprofit arm. “So you go out and do something and realize you can inspire other people to do the same.”

We had dinner in Lindau Michoacán, a state that President Biden visited this year. It was the first night of the Democratic National Convention, and the large dining room was packed. A Mexican football match is playing on the TV. Our table never looked at our phones to find out what was going on at the convention or even mentioned it.

But I turned the conversation to politics, asking Cepeda — a Democrat who lost her school board seat to a progressive challenger in 2022 — why she doesn’t plan to run for office again.

Every time I go to a meeting, I always tell them, ‘Look to the left. Look to the right. You’re looking for the next CEO, you’re looking for elected officials, you’re looking for presidents, you’re looking for business owners.

—Edgar Flores

“It’s a difficult situation,” she replied. Budget cuts. COVID-19 pandemic. Anti-vaxxers. “This led to an ideological split on the board,” she said.

“Erin received a lot of backlash from friends and people in the community because of her style,” Flores added. “She was always like, ‘I want everyone’s enter. I want everyone to have a seat at the table. That’s why I think she’s perfect for a project like LYLC. Because it’s all about inclusivity.

Our meals arrived – I had al pastor tacos, Flores had mole tacos, and Cepeda had ceviche tacos.

A painting outside the Lindo Michoacán restaurant in Las Vegas.

(Gustavo Arellano/Los Angeles Times)

The pair credits the Latino Youth Leadership Conference with changing their lives. Nevada’s Latino Chamber of Commerce started the campaign three decades ago with the goal of getting more Latinos into college and reducing high school dropout rates. At the time, Latinos made up 10% of the state’s population, according to census data. Today, that proportion is closer to 29%.

Students are divided into family, Adopt your own slogans and slogans. Friendships are lifelong, and alumni cheer each other on through life’s triumphs and tragedies.

“Every time I was exposed to anything that I considered power or money or whatever, there was always someone who came into your world and told you, ‘This is the way you should do it,'” Flores said. Attended in 2004. “This is the first time I’ve been to a conference where leadership has more to do with you and yourself than it does with anyone else.”

Cepeda, who was born in Inglewood to Nicaraguan parents and attended the event a year after Flores, said: “I had never been exposed to a leadership conversation where everything About you, like facing your own demons, facing your own problems, owning your own leadership.”

I had never been exposed to a conversation about leadership where it was all about you, like facing your own demons, facing your own problems, acknowledging your own privilege.

— Erin Cepeda

In 2014, Flores leaned on his conference alumni when he ran for state Senate. Shortly after he announced his candidacy, local politicians called for his resignation – they already had a candidate in mind.

“This is really weird and very anti-democratic,” Flores said with a look of confusion. “So I said, ‘Well, I think I’ll do this myself. So I ended up calling all these [Latino Youth Leadership Conference] Folks, like 80 to 90 people. We go for a walk.

Politicians are out of office. Flores faced no opposition and won every fight thereafter.

He’s proud of the alumni network — “miles and miles of roads in every direction” — that have helped empower Latinos in Nevada. He also recognizes the work that still needs to be done in the Silver State and beyond.

“I introduced pro-immigration bills every session,” he said, “and got killed every time. In my naive mind, I still have a hard time understanding why — like, it’s good for everyone. And then your heart breaks.

I believe that broken hearts in politics—unfulfilled promises of immigration reform, failing schools, rising housing inequality—are why Latinos are so apathetic to elections.

According to Census Bureau data, only 61% of Latino citizens nationwide are registered to vote in the 2020 elections, the lowest rate of any ethnic group. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey showed that 47% of eligible Latinos did not vote in the past three federal elections — by far the lowest rate of any ethnic group.

President Biden and Biden Nevada campaign adviser Maritza Rodriguez greet people as they arrive at the Lindo Michoacán restaurant before a radio interview on July 17, 2024 in Las Vegas.

(Kent West Village/AFP/Getty Images)

So how do you cure it?

“Go back to your roots,” Cepeda said. “You can make a difference in small things like helping your kids go to college, helping them cope with a broken world. These small changes can make a bigger difference.

This is a theme I heard time and time again when I was in the Southwest. This reminds me of the last line of one of my favorite novels, Candide. We must cultivate our gardens.

Candide leads an easy life, but years of trials and tragedies have left him increasingly miserable. He ends up on a farm, tired of the blind optimism of his mentor Pangloss.

I would open a pro-immigration bill at every meeting and get killed every time. In my naive mind, I still have a hard time understanding why – like, it’s good for everyone. And then your heart breaks.

—Edgar Flores

From the border to Arizona, New Mexico to El Paso, and now Las Vegas, everyone I talk to is growing their gardens. They did not ignore the outside world. They know the best way to improve it is to focus on what’s at hand.

I didn’t mention Voltaire, but when I asked Flores how he dealt with political disappointment, “Candide” came to mind.

“If I’m looking for the instant gratification of winning a bill, I’m making a mistake,” he said. “But if I allow myself to accept that I’m part of this pipeline — that I’m part of this process, eventually we’re going to do something, and I need to be there and get punched around so that the next person can achieve something — I think this makes sense.

At every Latino youth leadership meeting, Flores shares a parable about a baby learning to walk.

Erin Cepeda, left, and Nevada Sen. Edgar Flores outside Lindo Michoacan restaurant in Las Vegas. The two are alumni of the Latino Youth Leadership Conference.

(Gustavo Arellano/Los Angeles Times)

“When students are afraid of a question, I tell them, ‘Well, when you were a baby, why didn’t you give up? Did you back down? No! You were walking. It was hard. Because you hit your head, so in a row. You cried for five minutes, but you quickly stood up again and tried again.

He lets a beat pass. “I call it ‘the baby inside.'”

Cepeda and I laughed.

“Well, I have a son now,” Flores concluded, scrolling on his phone. “I recorded him doing it. I can’t wait to play it at future meetings.

He grinned. “He’s going to hate me for it.”

When I returned to my hotel room after we said our goodbyes, I listened to the Democratic National Committee’s speech. They all said it was a new way, a better way. No excuses. There is no turning back. The challenge of doing something.

I have a hard time falling asleep on my road trip. That night, I finally rested.