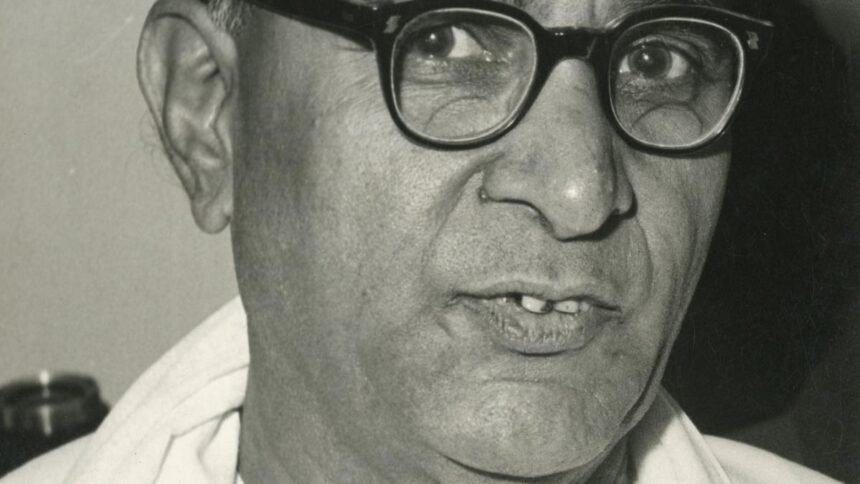

P. Ramamurthy of CPI (M) | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

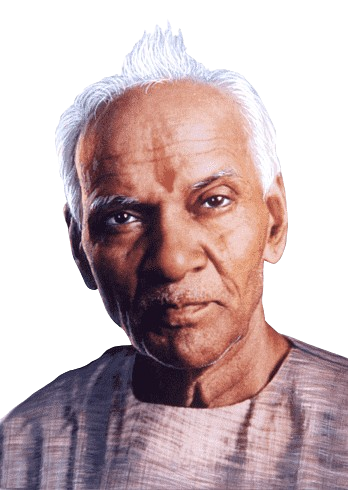

K Kamaraj | Image source: Hindu Archives

Within six months of independence, a major industrial uprising broke out in the textile industry of Coimbatore, an industrial city in western Tamil Nadu state. In one day, approximately 11,000 factory workers received layoff notices. This triggered a worker strike and a management lockout. The dispute lasted nearly five months. The riots were called off due to the intervention of Tamil Nadu Congress Committee chief Kamaraj and assurances from the government.

The South India Millers Association (SIMA) highlighted the issues at the management level. Representative figures on labor issues were P. Ramamurti, vice-president of the All India Textile Workers Federation and later a major leader of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and G. Ramanujam, general secretary of the country’s textile industry. INTUC) leader. In June 1952, Ramamurti raised the issue of retrenchment in a parliamentary debate. The Hindu covered the dispute extensively from January to May 1948, writing four editorials in the six months since January of that year.

New workload standards

On the last day of 1947, the government accepted and published the Interim Report of the Textile Standardization Committee, which set out new workload standards. This was also the time when the minimum wage became a reality across the country. The Central Legislative Assembly (the predecessor of Parliament) passed a bill on minimum wages in 1946. Workers’ wages were more than double those before the revision. During World War II, factories hired more workers. After the war ended in 1945, management concluded that additional workers were no longer needed. The factory began implementing the award in April 1947. Some of them closed their businesses.

The night shift has changed

It was against this background that the Standardization Committee’s workload report prompted management to assess that 11,200 workers had become surplus workers. On January 5, the factory posted a layoff notice, informing employees that the notice would take effect on January 20. Initially at 7am it was thought workers were unhappy with the night shift starting an hour earlier. The labor department advised factory owners to restore the original hours. As the workers refused to quit, management realized that the real reason for the strike was layoffs. SIMA said in a press release issued on January 9, “Factory owners have pledged to the government and labor leaders to re-employ as much of the remaining workforce as possible through an extra day a week or extra shifts. Whenever possible, we will Explore.

As the problem escalated, the government attempted to mediate. But on January 20, its efforts to announce a compromise failed. It describes conditions in 11 factories: in nine of them workers refused to do what they had been doing before; in one case a sit-in took place; in another, they were unable to work. Three days later, the matter was brought to parliament for discussion. Industries Minister H. Sitarama Reddi held labor leaders responsible for the problem and said they were unwilling to accept the committee’s recommendations. On January 27, the management of 27 factories announced a shutdown based on the decision taken at the SIMA meeting two days earlier. Factory owners in Salem and Tiruchi followed suit.

protest in front of parliament

The deadlock lasted for two months, with a dozen workers demonstrating once in front of the secretariat chamber. On March 20, the government asked factory owners to resume operations within two days as some workers wanted to return to work. Owners responded well, but not all workers returned. SIMA clarified that since 9,250 of the 11,200 workers had been promised re-employment, the “net redundancies” were 1,950, which had been hired to meet wartime needs and had “no direct relationship with the industry at all”. Meanwhile, the workers’ cause has found sympathy with the think tank Indian Institute of Current Affairs, which has set up its own group to study the issue. The institute urged the government to put the standardization plan on hold “in the interest of labor and the public” to be reconsidered by a new committee.

Kamaraj stayed in Coimbatore for two days in early May and met representatives from both sides. He later called on the government to revise the revised workload and ask workers to return to work. Later, the workers announced the withdrawal of the strike. The government insists that the revised workload should be given a fair trial and can be appropriately revised if there are difficulties. Most factories began operating a third shift and, in fact, initially reported staffing shortages. Owners have also set up “reemployment exchanges” for the unemployed. All these developments ended the crisis.

Published – November 8, 2024 12:37 AM (IST)