Recently published in national medical journal of india The need to introduce a pool of mid-level healthcare providers (MLHPs) in the health system was highlighted to bridge the shortage of doctors.

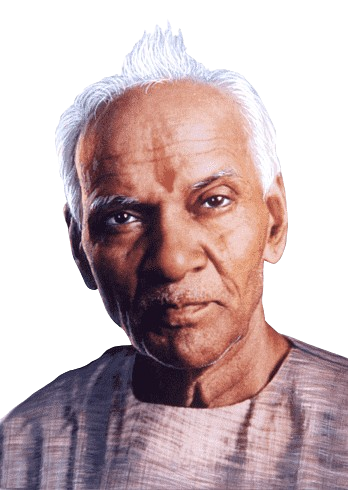

The paper, written by public health expert and independent researcher Soham Bhaduri, states that the MLHP model can create win-win combinations in healthcare, benefiting patients, doctors, healthcare financiers and society at large.

To compensate for the shortage of physicians, some countries around the world have introduced a cadre of MLHPs into their health systems to assume many of the routine responsibilities of physicians. However, in India, mainstreaming of MLHP has been repeatedly resisted by the organized medical community.

“Policymakers need to work to increase acceptance of MLHP within existing health professions, demonstrate its complementary role in patient care and alleviate long-standing concerns such as quackery. Incorporate professional practice models that ensure long-term growth and career development , MLHP can support India’s progress towards achieving and sustaining universal health coverage,” Dr. Bhaduri said in the paper.

Severe shortage of doctors in rural India

The “India Health Dynamics (Infrastructure and Human Resources) 2022-2023” report released by the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in September this year shows that community health centers (CHCs) in rural areas of India face a shortage of nearly 80% of experts in 2023. March 31, year.

This previously released Rural Health Statistics report shows that as of March 2023, there are only 4,413 specialists out of 21,964 required in rural health centers, a shortfall of 17,551 (79.9%).

There are 5,491 rural community health centers in 757 regions across the country, each requiring 5,491 surgeons, internists, gynecologists and pediatricians. However, the report shows that rural community health centers have a surgeon shortage of 4,578 (83.3%), with only 913 surgeons on staff against the required number of 5,491 surgeons.

Similarly, there is a shortage of 4,078 gynecologists (74.2%) in rural health care centers, with only 1,442 of the 5,491 needed; there is a shortage of 81.9% of doctors, with only 992 available. A similar trend is seen among paediatricians, with only 1,066 paediatricians available in rural health centers, a shortfall of 80.5%.

This isn’t just a problem for a handful of states in the country. Even countries that typically perform well on health indicators face these problems. In the case of Karnataka, the number of doctor/medical officer vacancies in rural primary health centers in the state has increased from 196 in 2005 to 340 in 2023.

As far as specialists in community health centers are concerned, only 451 positions have been approved out of the required 758 specialists. The report said that 178 of these posts were vacant, resulting in a shortage of 455 specialists in rural CHCs in Karnataka.

In fact, staff shortage is a long-standing problem in public hospitals. In 2022, the Karnataka Health Vision Panel noted that there is a huge disparity in the distribution and availability of manpower for specific specialties in government hospitals. It recommends the development of clear health human resources (HRR) policies.

MLHP case

talking hinduismDr. Bhaduri said that the paper explores a new case of MLHP in India in light of some recent developments in the Indian healthcare sector and possible future scenarios.

“Evidence shows that, in some circumstances, MLHPs can provide care of the same quality and safety as physicians at lower overall cost in a range of settings. It has also been found that, in addition to improving access to health care in underserved and rural areas and In addition to their clear contribution to utilization, they also perform as well or better on patient satisfaction and trust. Evidence also suggests that MLHPs are less likely to immigrate and more likely to remain in underserved areas—both standouts. The problem has long plagued the health system of doctors,” he said.

In India, the central and state governments have conceived of allopathic bridge courses from time to time to address the shortage of doctors in rural areas. In 2010, a proposal to shorten medical degrees in rural healthcare was tabled and supported by the Planning Commission. States such as Assam and Chhattisgarh have successfully deployed state-level MLHP cadres to improve access to primary health care in rural areas. However, Dr. Baduri said that attempts to mainstream MLHP have been met with resistance from organized medicine time and time again, mainly because they exacerbate quackery and constitute discriminatory treatment of rural citizens.

Corroborating Dr Bhaduri’s views, G. Gururaj, head of the Karnataka Health Vision Group and former director of NIMHANS, said MLHP can facilitate India’s progress towards achieving and sustaining universal health coverage (UHC).

Dr. Gururaj said that several recent policy and legislative measures have given new hope for a systemic revival of MLHP in India, with the central government’s Comprehensive Primary Health Care (CPHC) guidelines under the flagship Ayushman Bharat Mission making provision for deployment of community health sub-centres. Officer (CHO). He said they could provide more primary care services and refer them to doctors for further treatment.

“Since MLHPs are located at health sub-centres close to the community, continuity of care is ensured for patients. They are not supposed to diagnose conditions/diseases but provide preventive and promotive care while ensuring that patients who have been diagnosed by doctors receive appropriate care, especially follow-up care. They work closely with ASHA staff and assisted nursing midwives (ANMs) and have a good understanding of the community. “There will be no overlap in their functions with the doctors,” Dr. Gururaj noted. .

Is charlatanism legal?

However, the Indian Medical Association (IMA) has been opposing the introduction of MLHP, claiming it would only legitimize the practice of quackery in the country.

“This is nothing but quackery. Allocating MLHP to rural areas amounts to discriminatory treatment of the rural population. Will these policymakers agree to undergo treatment under MLHP? asked IMA National President RV Asokan.

On the shortage of doctors in rural areas, Dr Asokan said there are currently enough medical professionals. “According to a statement made by former federal health minister Mansokh Mandaviya in the Lok Sabha in February this year, the country’s doctor-to-population ratio is 1:834, which is better than the World Health Organization’s standard of 1:1,000. According to his It stated that as of June 2022, a total of 13,08,009 allopathic doctors were registered with the National Medical Council and the National Medical Council (NMC).

Dr Asokan claimed that there had been no recruitment of doctors through the Public Service Commission in the past 10 to 15 years and “the government only appointed doctors on an ad hoc basis through the National Health Mission (NHM) and paid them about Rs.” Doctors were forced to sign indentures, which was nothing but slavery. In the absence of long-term recruitment, it is wrong to say that doctors are not ready to work in rural areas,” he asserted.

Published – November 7, 2024 at 5:30 pm (India Standard Time)